Somil Kumar | March 15, 2022

Survey 101: Conducting a Needs Assessment Survey

M.A.P’s Sexual and Gender-based Violence (SGBV) project sought to work with survivors from displaced and other vulnerable migrant communities to fuel a transformative change in current service delivery approaches. One way it does this is by developing India's first remote and mobile SGBV case management system, including the creation of a digital tool for survivors and at-risk women to use.

When considering the kind of interventions to improve the ecosystem and augment structures that provide support to survivors, we first had to overcome a more fundamental problem—what is the understanding of SGBV within communities? What do individuals and communities think about causes of SGBV, and structures that are meant to support women? What have the experiences of individuals and communities been? We realised that for our project to have a solid foundation, we needed to investigate these questions in a sensitive manner with our target community.

Designing the Survey Schedule

Since we were broaching a highly sensitive topic, we needed to carefully identify the amount of information we were seeking from respondents, having assured them that this would be kept confidential. This included personal basic information and documentation held, knowledge of SGBV related laws and incidents, knowledge of support structures, digital capacity and a desire for digital interventions for SGBV issues. When considering, for instance, the knowledge of SGBV laws, should we focus on a functional knowledge or consider as well basic legal knowledge? Similarly, when attempting to gauge awareness of institutions, which ones were to be considered: should we limit ourselves to government institutions or even include community organisations and NGOs?

Given that one of the aims of the SGBV project was to consider what digital tools interventions could be useful in this space, our survey sought to understand capacity within the target communities. Beyond simply ascertaining the presence of phones or smart phones, given the nature of intervention we sought, it was important to consider nuances within capacity. For our survey, it was important to not only understand how many women had access to phones and smartphones, but whether they had sole access to these devices, whether they accessed the internet and what was their pattern of use for their phones. Further, were respondents aware of digital applications and what types of such applications they had used?

Surveying digital capacities and the need for a tool to assist survivors of SGBV necessitated feedback to ensure the app contained features that were sensitive to their needs and requirements: language, privacy, audio playback and illustrations for low-literacy users, an easy to navigate interface for those with low digital-literacy, among others.

To ease the interviewee into the schedule we divided the questionnaire into different parts, created as a mix of both open-ended and close-ended questions. The sections included:

Personal Information;

Documentation;

Awareness of SGBV;

Awareness of SGBV support structures and knowledge of experiences with them;

Digital Capacity and Desirability of Digital solutions.

The first section involved the collection of demographic information to build the profile of our respondents. In using different demographic metrics as a variable allowed us to reach different conclusions on the relationship between gender, literacy levels, employment status, age or other such metrics and knowledge of SGBV and SGBV support structures. The idea behind understanding these relationships was also important to the scope and design of the SGBV project and how we could possibly tailor our proposed solutions to have better reach and more impact.

While the need for sections on awareness of SGBV and related support structures is fairly obvious, it was important to consider not only respondents’ awareness at a basic level but gauge whether they would access any of these laws, institutions or support structures, and if they had any prior experience with them.

Equally, it was important to understand whether respondents looked on these laws, institutions and structures as potentially helpful and to understand from them what impediments exist for engagement with them.

Reaching out our Potential Respondents

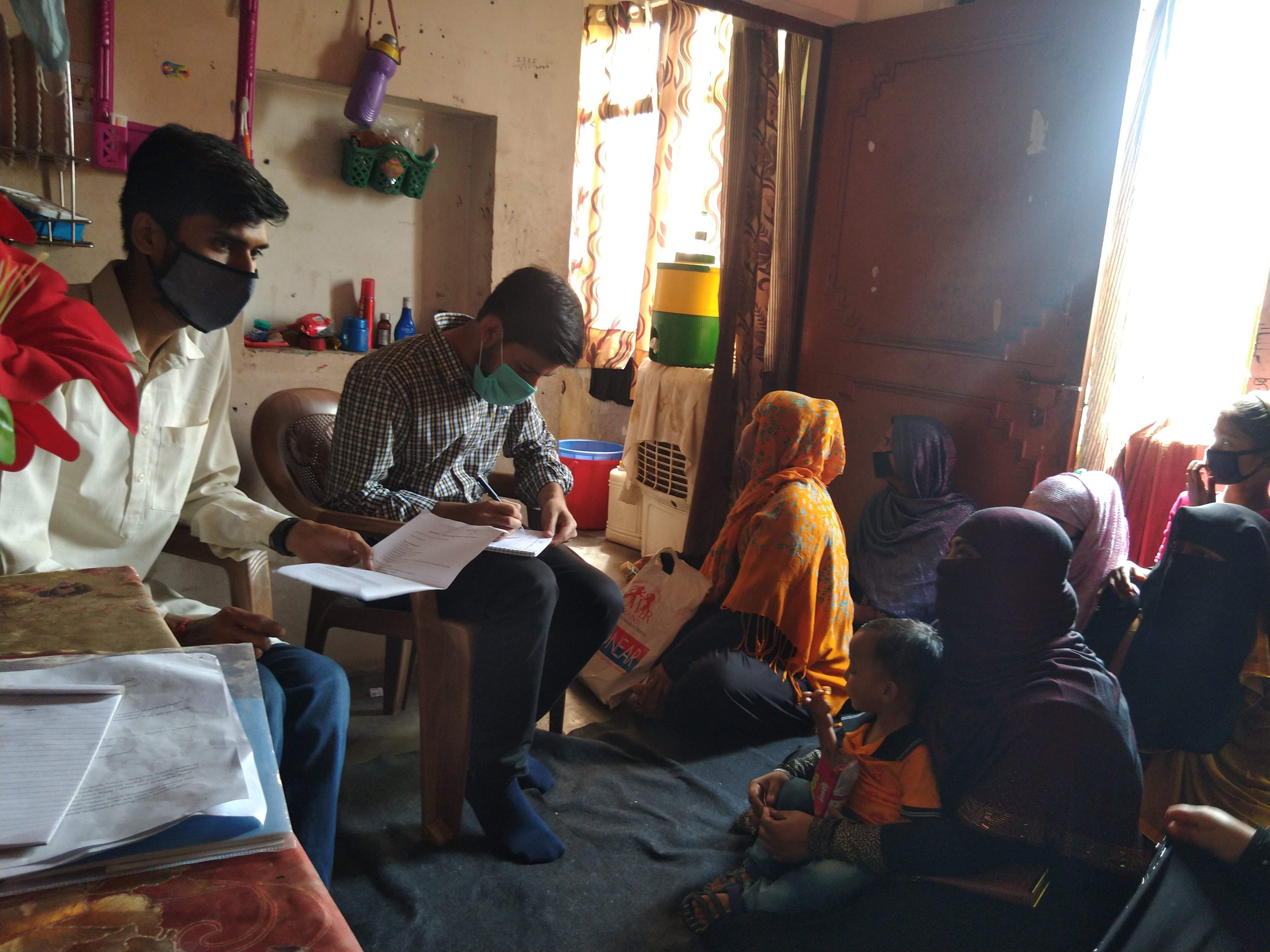

Once the survey schedule was ready, the next step involved going into the identified settlements and speaking to community members. As mentioned earlier, all respondents were assured of confidentiality before the interview began.

The reasoning highlighted above would have meant little without adequate and considered engagement from members of our target communities. While we were dependent on the willingness of respondents, as a team conducting the survey we had to account for the difficult in getting individual respondents to speak to SGBV related issues.

Overcoming reluctance across communities to address SGBV issues was a challenging task that necessitated the use of various rapport building strategies to convince respondents that our survey would not only be in service of trying to improve SGBV related institutions across these communities but that we would protect the privacy and confidentiality of respondents. Further, particularly when speaking to survivors or respondents that knew survivors, we had to engage with empathy as well as with a desire to understand the experiences that survivors of SGBV have had in target communities.

Conducting a Survey in a Pandemic

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were compelled to conduct a portion of our survey over the phone and not in-person. This presented a whole different set of challenges to rapport building as we had to convince respondents not only of the legitimacy of such a sensitive and personal survey but that of the organisation being one that was working in earnest to resolve SGBV related issues in target communities. Undoubtedly, engaging with respondents on SGBV issues and eliciting useful and detailed responses was made much harder in the pandemic. Not all respondents were equally forthcoming and many were reluctant to delve into details. Several were averse to acknowledging knowledge of SGBV incidents in their communities.

Since our target communities also included forcibly displaced migrants, we had to tailor our approaches to each of these communities. We had to ensure that we left plenty of room to ask follow-up questions, if naturally flowing in the conversation, so that we didn't miss out any crucial information.

Some Crucial Findings…

“The family usually does not let the woman complain or seek help. They blackmail her emotionally and sometimes even physically restrain her.”

— Sulekha, 55 (name changed)

It was instructive to find that most respondents wanted to engage with the survey because they believed that improving SGBV literacy in their communities is important. In addition, it was encouraging that respondents were enthusiastic about any tools, digital or otherwise, that could help them expand their knowledge of issues and potential solutions. It was also significant to note that due to the pandemic, there has been a growth in digital capacity across communities and on a range of issues. Digital solutions that are designed well could significantly alleviate existing issues within communities – not only SGBV but perhaps other areas as well.

Even with the challenges above, we felt that the survey was not only successful but also useful in terms of takeaways it can provide for similar efforts, that can be scaled up, and bring about actual transformative change. We gained useful responses allowing us a nuanced understanding of SGBV knowledge, engagement with support structures and scope for digital interventions.

Also identified were key point persons within the community, who were committed to bringing about social change within their settlements. These Focal Point Persons would become crucial stakeholders within the Talika Network (See 'Talika Network: NGOs and Focal Point Persons')

For more information on the findings of the survey, please read our May 2020 report: Sexual and Gender-Based Violence and COVID-19: A Survey of Six Settlements across Delhi-NCR